| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

The major theme of Chicago geography is "mind over matter." We see a somewhat bungled but enthusiastic attempt to impose order on nature's blank canvas. The city is reinvented as a sort of warehouse (or stockyard) for people. The rectilinear grid plan of horizontal and vertical lines is pushed to its practical limits.

Grid planning is nothing new. Some Mesopotamian cities used it at the dawn of civilization. Most of the 11th-century Tale of Genji takes place in rectilinear Kyoto, complete with numbered avenues down which the courtiers walk as naturally as any Manhattanite. So we cannot entertain for one moment the idea that Old World cities are sprawling and disorganized because nobody could think up a straight line. Nor is it really plausible to blame poor technology or surveying equipment. Surely any literate society that cared to investigate the problem could have obtained fairly good results with some combination of trigonometry, fixed-length chains, compasses, and observation platforms. Tedious as this work may be, it does not require staggering feats of insight.

Rather than ask why city planners failed to employ simple and logical methods, we must ask how often in history planners were called upon to develop large contiguous areas in the first place. Genji's Kyoto was rectilinear because the entire complex was purpose-built as the new imperial capital, for a captive audience of ministers and their staffs, in consultation with learned astrologers who had studied great Chinese cities, hoping to protect the health of the emperor by selecting, for instance, the most auspicious width for a city block. It is far from shocking that the same pains were not taken in every municipality! Of course, population pressure in any society requires an intelligent response to prevent deplorable living conditions. But keep in mind that not until 1800 or so did the world population reach one billion. Cities of a million people have existed since antiquity, but none got very far above that healthy ceiling until the 1850s (when Europe began to discover the effect of lower death rates: too many people). In 1900, less than a quarter of the world population lived in urban areas at all. Not to oversimplify, but the pre-industrial world sounds pretty spacious. In the absence of certainty that a large number of people will imminently descend on a given area and require accommodation, an expensive master plan seems out of place.

I have not even mentioned what may be the most important consideration. Even if a master plan is called for, a grid plan is not appropriate when the city is founded on interesting terrain. A road that curves to stay on high ground is more useful than a straight one through a marsh. Steep hills, multiple intersecting rivers, a complicated coastline, and other natural obstacles may serve to divide a city into sub-units, each of which has an internal order, while the city as a whole lacks a consistent scheme.

A patchwork, piecemeal approach is precisely what we observe in the following maps from Tokyo, New York and Detroit. Note the islands of local organization, the interesting borders where one scheme gives way to another, and the way in which a major street seems to bend smaller streets to its will, like a heavy sun distorting the fabric of spacetime. We see plenty of neatly-drawn grids, but never a single master grid.

The highly unusual conditions that could cause a large area to be carefully, consistently gridded out into rectangles were achieved in the United States around the turn of the Nineteenth Century. The new country was rapidly obtaining the rights to an enormous swath of territory (mostly flat) between the Appalachians and the Rockies, yet that land was not actually occupied by American citizens in any significant numbers. The East Coast was not crowded per se, but the population did have large rootless, restless elements. Several outcomes were seemingly possible at this crucial juncture. There could have been a complete Black Friday free-for-all, with every family claiming as much land as it could defend by force. (This would probably lead to a new Europe, fractured into volatile, squabbling alliances.) Or there could have been a reconciliation with the surviving Native Americans, perhaps featuring multiethnic settlements in areas of high commercial activity. It is fascinating to envision an alternate-history Chicago that grew organically around DuSable's original trading post, and wound up largely resembling the above images.

But Thomas Jefferson, an idealistic intellectual like many of the founders, had long anticipated the problem of distributing land to a large number of people in a short time without losing their patience or allegiance, and he acted quickly to set his plans in motion. Envisioning an agrarian paradise of self-sufficient, hard-working families, in which peace would be kept by making it clear that there was plenty of land to go around, he created a system that would not only meet the needs of the living generation of claim-seekers, but could easily be extended across the vast continent and outlive him by many centuries.

His plan was simple enough that the Mesopotamians could have understood it. The entire country should be covered with an imaginary grid of squares one mile to each side. Roads should eventually be built along most of these dividing lines; until then, they could be marked with stakes and posts. Anybody who desired a parcel of land could visit any government agent and acquire one of these square-mile "sections" (or a portion thereof) for an appropriate price. He and his family would then travel west and locate their new land, which would be as easy as finding an address in today's Chicago, thanks to the logical system of horizontal and vertical lines crisscrossing the plains and forests.

Official surveying of the Northwest Territory (today's Midwest -- see "Northwestern University") began as early as 1786. The work proceeded roughly as follows. The best surveyors on the federal payroll would concentrate their energies on drawing very long, straight master lines called baselines (horizontal) and meridians (vertical). These are like the X and Y axes you draw on graph paper before attempting the graph itself. The 350-mile "Third Principal Meridian," for instance, splits Illinois vertically from top to bottom, and provides the template for other vertical roads in the vicinity. The federal surveyors would keep moving west after completing these reference lines, while a new commission of Illinois surveyors would then elaborate upon the existing work by drawing out counties and townships. You can see how the level of detail in one region of the map would keep increasing over time, while responsibility for the measurement becomes a more and more local concern, up to and including the end goal: a friendly farmer takes over an individual parcel and makes its boundaries known to the neighborhood.

It is truly remarkable that this project unfolded almost exactly as Jefferson envisioned it. Keeping in mind the importance of circumstances (i.e. the extraordinary opportunity available to Jefferson and not to other politicians in history), it is difficult to think of a person who was more successful in altering the literal face of the earth according to his will.

We all know what a county is, thanks to county courthouses, county fairs, and county boards. And you will find that a map of the counties of Illinois looks a lot like the map of the states of the USA: fairly random, with some large units and some small; some straight lines and some river boundaries. What happened to the logical Jeffersonian grid? It is just hiding one level of organization down, at the level of the township.

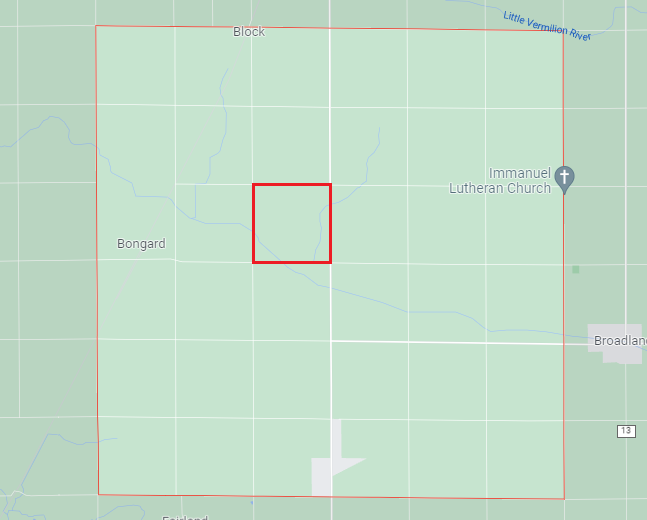

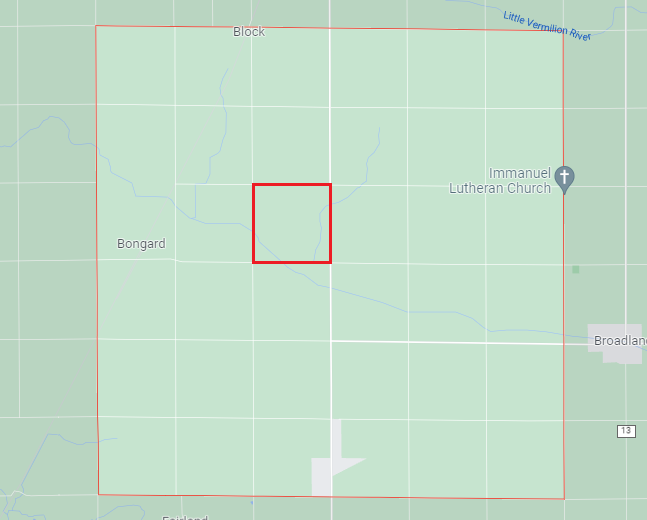

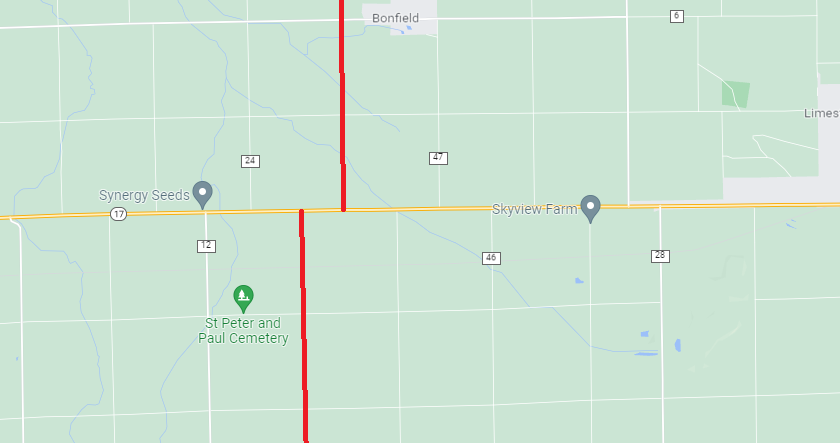

Counties are made up of townships just as states are made up of counties. A typical township is a square six miles to each side, which means it contains thirty-six "sections" of one square mile each. Thus it is sections, not townships, that catch your eye from an airplane or a satellite. Townships at the corners and edges of a county may be excused for deviating from the standard shape, but here is a model township in Southern Illinois, with one section marked in bold red. This township is just one out of about thirty townships making up this particular county, and there are 102 counties in the state, which is just one of fifty in the nation. The concept of nested hierarchical categories, so important in scientific systems, is well-developed in the American countryside.

It would have been highly convenient if one square mile was precisely the amount of land that one 19th-century American family wanted to farm. That would have been the cherry on top for Jefferson -- especially if he sold each section for one dollar apiece. But in practice the government could not sell as many full sections as it first hoped; fractions of sections proved easier to sell, and terms like "quarter-section" (i.e. a square half a mile to each side) were in common circulation at that time. For more precise applications, the acre was a convenient unit. 640 acres make one full section, 160 acres make a quarter section, and 40 acres make a quarter-quarter-section. The freed slaves who were promised 40 acres and a mule were therefore anticipating one sixteenth part of a square mile: theoretically sufficient for comfortable subsistence farming, but by no means a vast country estate, as a square one-quarter mile to each side can be crossed on foot in five minutes.

Perhaps you are wondering what any of these countrified terms have to do with Chicago geography. The fact that they are related is the entire point that I want to make. Chicago does not exist outside of this rational dream of meridians, baselines, sections, townships, and acres. Rather, the entire sprawling Chicagoland area, home to over nine million people, is just one small portion of the grid which happens to have been "filled in!"

It's true -- by the time Chicago's founders were building the first permanent roads and city blocks downtown, they were already trapped in the web of Jefferson's grid. The proper authorities were on hand to ensure that nothing got out of sync with the state's master grid plan. People who bought land near the young city were limited to specific rectangular parcels of specific sizes, in exactly the same manner as farmers downstate establishing their family holdings (though of course the monetary value of a section near Chicago began to rise astronomically as the city developed). Years before anybody walked up and down Pulaski Road, and a century before it passed through the heart of residential Chicago, it was preordained that a road would be built precisely along that line, not because it was somehow a good place for a road, but simply because of the placement of the Third Principal Meridian. Even today you can drive along a country road that separates two rural townships, only to wind up on a busy street that separates two Chicago neighborhoods.

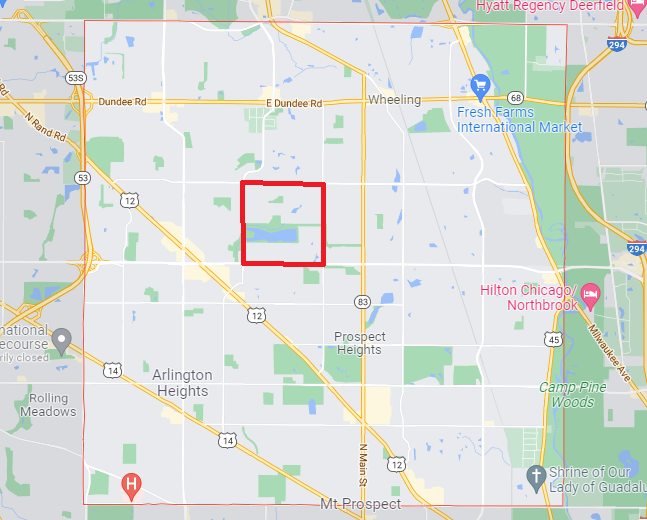

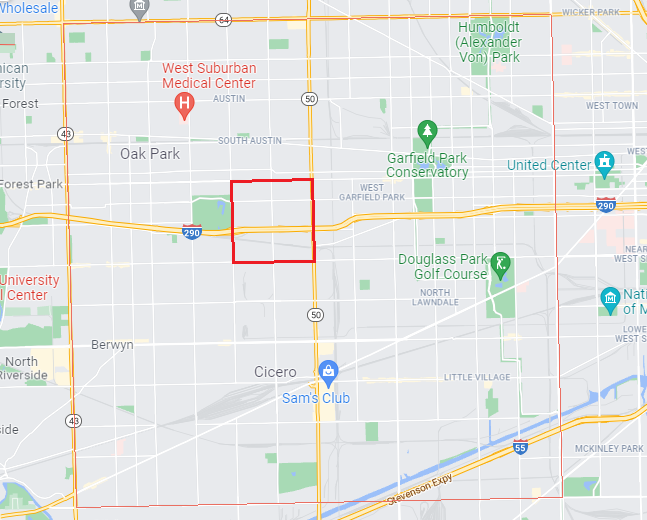

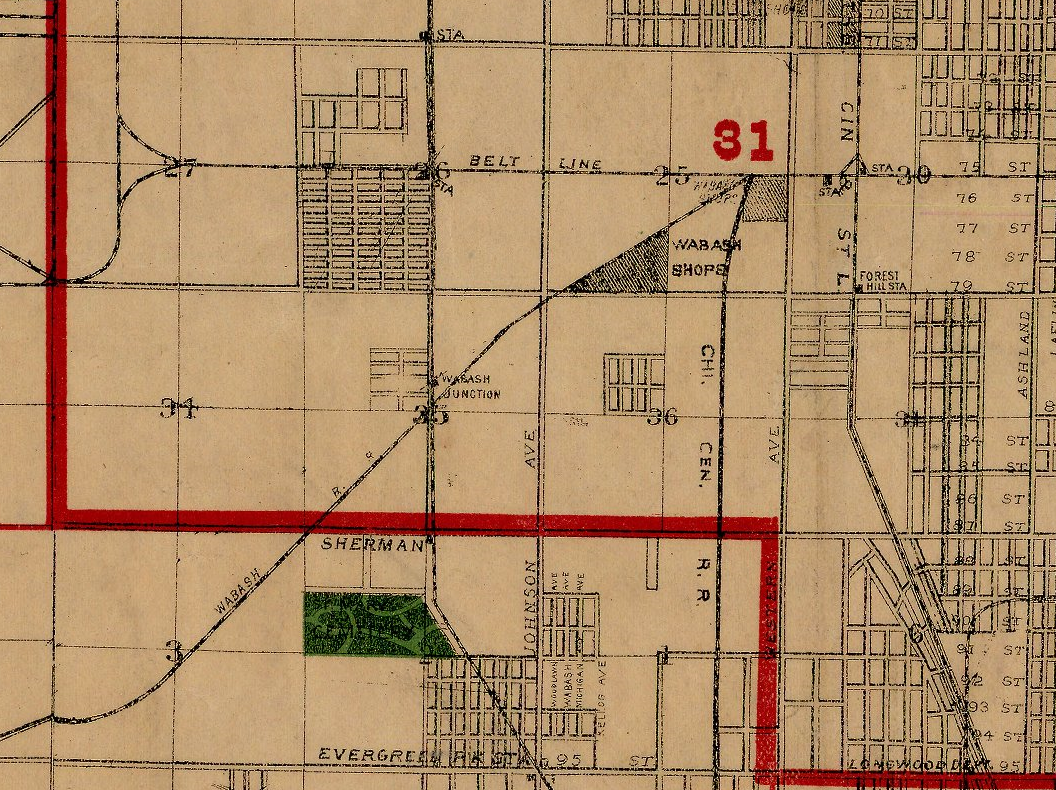

Compared to New York and Tokyo, our city seems to have been built backwards: instead of a city evolving to meet the needs of a population, we see a population working to fit itself into the preexisting squares of the city! Is there not something eerie about the lonely square towards the left of this map which has been feverishly divided into blocks?

I mentioned how the country is divided into states of various shapes, and states are divided into counties of various shapes, yet the logic of the grid plan (which theoretically divides the whole landscape into square miles) is always working beneath the surface. In much the same manner, Chicago is made up of countless neighborhoods and sub-neighborhoods, large and small, round and square, fitting together along uneven, disputed borders -- but the true organization is found in the grid plan.

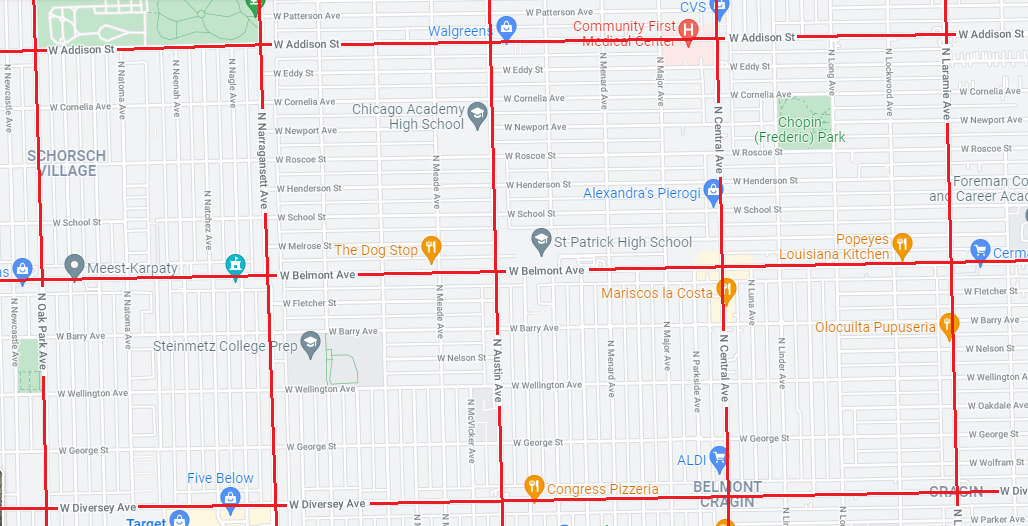

The basic building block of Chicago is not the section, but the quarter-section: the square half a mile to each side (160 acres). In the center of the urban area, we expect to find a major street at every half-mile interval, whether we look north and south or east and west. These major streets are often lined with commercial establishments, bus routes, large apartment buildings, and so forth, while the interior is generally reserved for family homes, two- and three-flats, schools, parks, and churches. Rivers, railroads, highways, and old Native American trails may cut across the square and disrupt its logic, but they cannot obscure the fundamental half-mile grid.

Large areas of the current City of Chicago were once independent towns with their own address systems and street names. Today, they have been brought into the fold of a single address system. Edward P. Brennan is usually credited for this feat, working in the 1900s and 1910s not only to shout down objections that changing established addresses was an unreasonable burden on citizens, but also to identify precisely what changes needed to be made.

Aiming for simplicity and universality, Brennan imposed a single pair of X and Y axes on Chicago, with a "zero point" at State and Madison downtown. State is the vertical street that divides East from West; Madison is the horizontal street that divides North from South. Neither of these streets is a township line; the fact is that no two township lines intersect in or near the Loop district (which was naturally chosen for its location near the river mouth), so Brennan's hands were tied on that point. But he did the next best thing by choosing two streets that are both section lines: State lies exactly three miles east of the township line at Western Avenue, while Madison lies exactly two miles south of the township line at North Avenue. (Can you guess how North and Western Avenues got their names?)

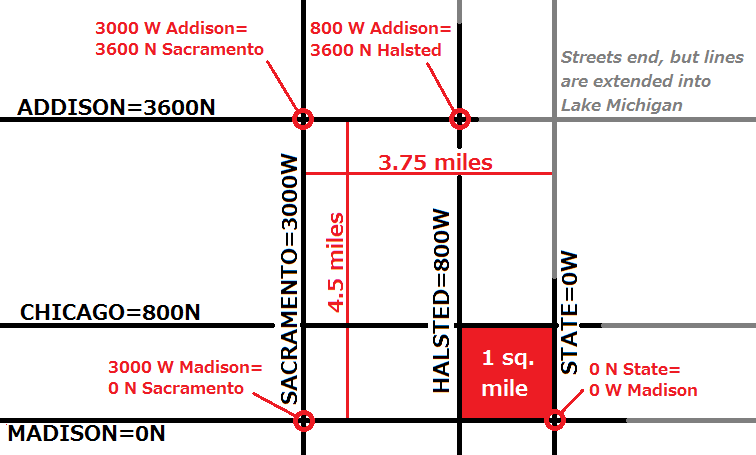

As you probably already know, an address like 3000 West Addison is trying to tell us that our location of interest is on Addison, 3000 "units" due west from the zero line of State Street. These units lack an official name, unless "house numbers" will do. What we must remember is that 800 of these units correspond to one mile in Chicago, such that the difference between two addresses on Addison, divided by 800, should give us the mile distance between the two points. For instance, 3000 West Addison should be 3.75 miles due west of State Street.

What may not have occurred to you is that thanks to Brennan's logic, there is a sense in which Addison itself "has an address." Let me explain what I mean. As Addison is located four and a half miles due north of Madison (to which it is parallel), it is always 3600 "units" north of that zero reference line. In other words, "Addison" and "3600 North" are interchangeable. Vertical streets can be described in a similar way. If we travel to 3000 West Addison, and observe that we are on the corner of Addison and Sacramento, we must conclude that Sacramento is equivalent to 3000 West. Every point on Sacramento is 3000 "units" (3.75 miles) west of State. Next time you are at a stoplight, look at the large street signs mounted on the bars and you'll see this name-number system in use. For instance, the sign for Addison should have "3600N" in smaller letters below.

Now we are equipped to quickly calculate the distance between any two points, as long as we know how to translate street names into numbers. For instance, to get from Halsted (800W) and Addison (3600N) to Sacramento (3000W) and Madison (0N), we must travel ( 3600-0 / 800 ) = 4.5 miles south, and ( 3000-800 / 800 ) = 2.75 miles west.

So far, I have described the Jeffersonian and Brennanian(?) systems in ideal terms. But now that they are reasonably well understood, we have to face facts: neither one of them is anywhere near perfect. The attempt to impose order was real, and the form that things took was an expression of that desire, but these are not the men who have proved Plato wrong about the difference between the perfect circle we imagine and the flawed circle we actually draw.

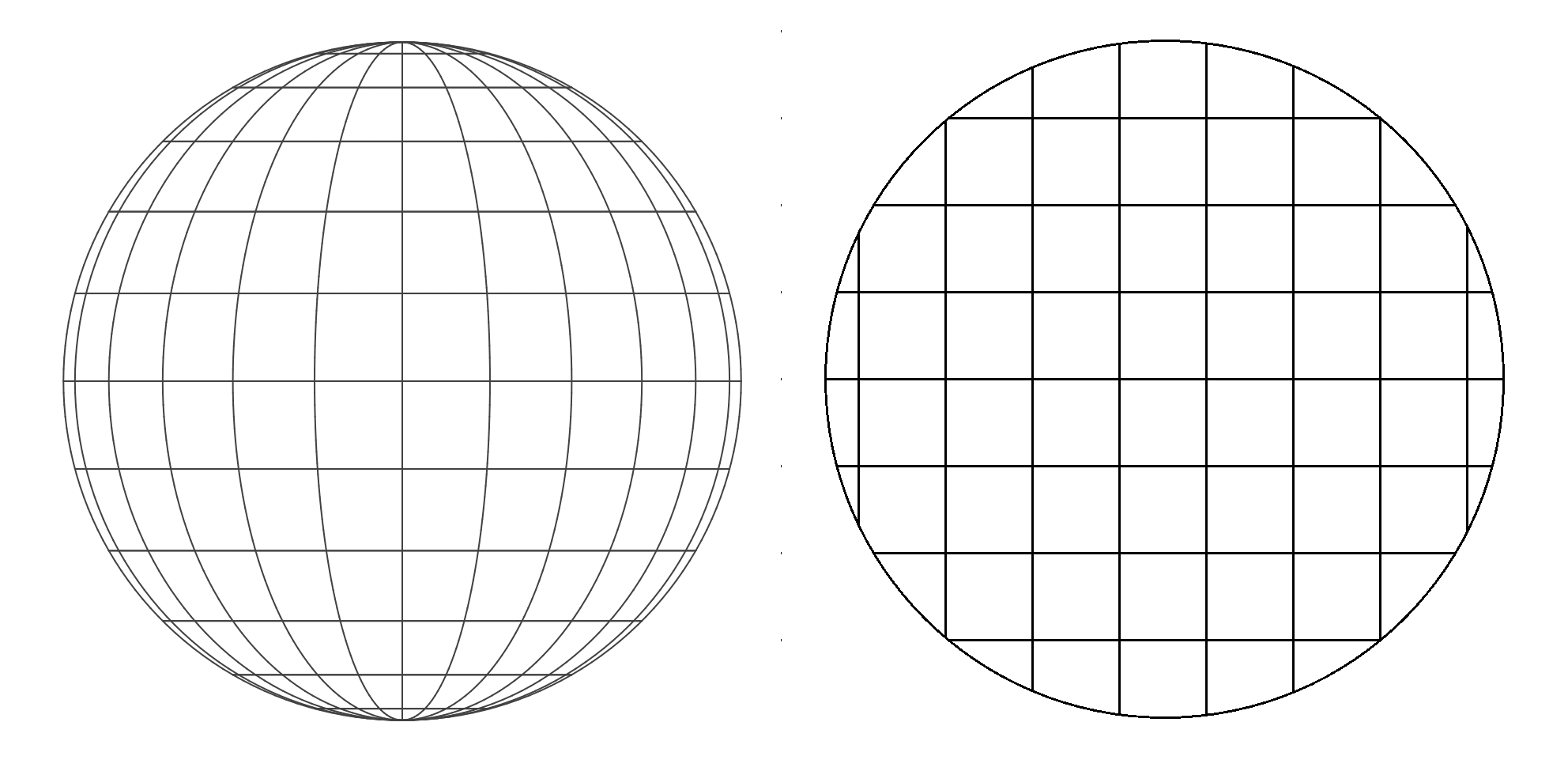

The biggest criticism of the Jeffersonian grid is hard not to phrase as a compliment: it was so ambitious, and covered so large an area, that the curvature of the earth, which can be safely ignored in the vast majority of human activities, became a complicating factor. It is impossible to cover a spherical surface with squares! You cannot simultaneously make all angles ninety degrees and keep all the lines running due north, south, east and west. The horizontal lines are no problem; lines of latitude like the equator and the Tropic of Cancer are truly parallel. But true north-south verticals must be allowed to converge as they approach the poles, meaning the left and right sides of a square cannot be parallel. That demotes the square to a trapezoid.

Personally, I think it would have been delightful to draw these trapezoidal sections. If you accept that townships and sections get skinnier as you travel north, and accept that intersections of section lines are not perfectly perpendicular, there is no longer a contradiction. But Jefferson's surveyors took the prosaic route. They preserved "real" squares, rejected the notion of smaller sections for Wisconsin than for Illinois, and accepted the consequence that every now and then, both to correct for curvature and to cover up their own mistakes, it was necessary to dogleg the vertical section lines and break up their continuity. This seems to be done at the edges of two townships where the accumulated error has approached half a mile.

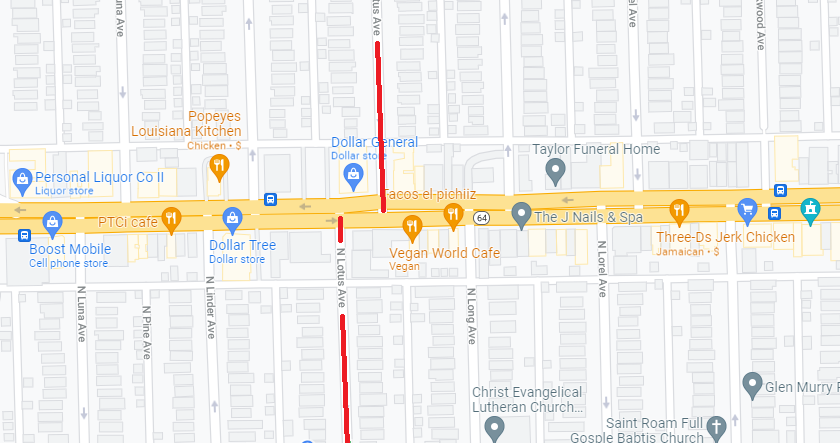

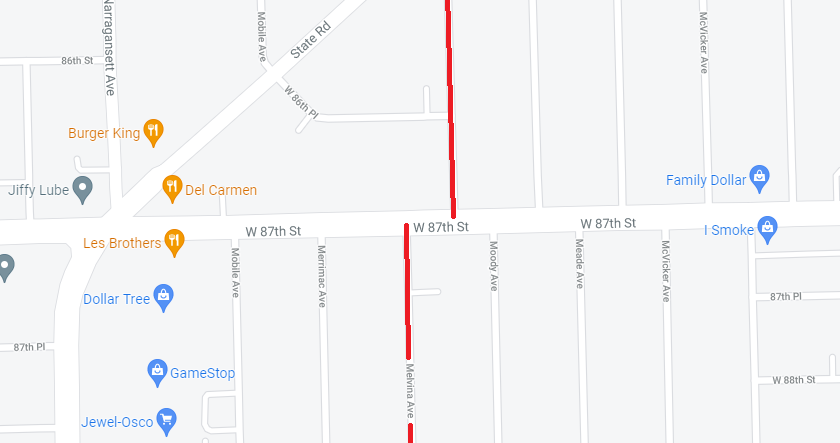

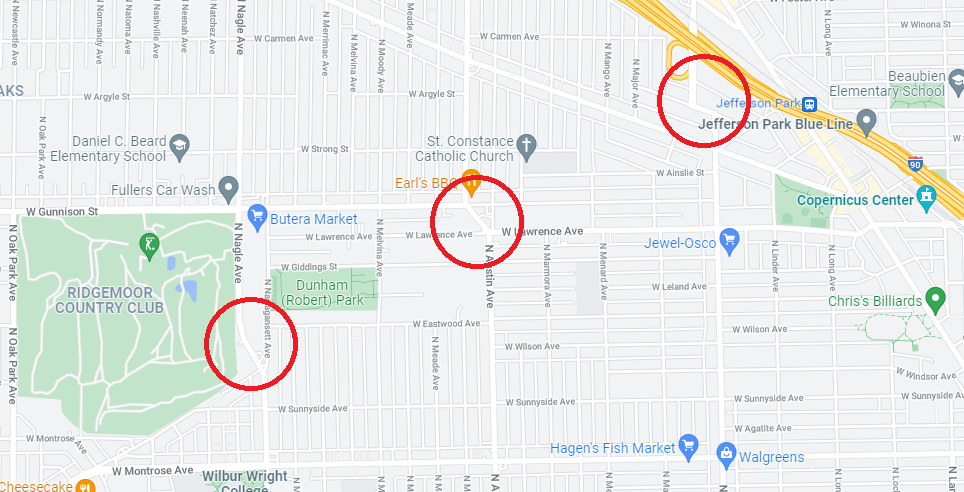

Isn't it disappointing? We're back to "islands of local order" all over again! This even happens in Chicago (not because of curvature, but purely through human error). North Avenue and 87th Street are both township lines plagued by mismatched streets. I'm guessing these errors date from a time of intense real estate speculation, with two separate crews (one above, one below) working fast to prepare lots for sale and development. Making a buck didn't require the teams to coordinate their efforts.

Speaking of human error, I hope nobody got ripped off buying some of these sections at the far edges of suburban townships! (Apparently surveying errors tend to "accumulate" in the upper-left-hand corner.)

Let me just mention that if Thomas Jefferson had been born in the world of Final Fantasy VII, where going off the top of the map makes you reappear at the bottom, he could have marked out perfect squares to his heart's content. But that world is a torus, not a sphere!

I could point out hundreds of "shoulda-coulda-woulda" artifacts around Chicago, where miles fall short and lines have to change to stay the same. Happy squares are all alike; each unhappy square is unhappy in its own way, but a catalogue of these errors is not thrilling. We should, however, distinguish between squares that failed at being squares, and squares that never set out to be squares. If the aberrant behavior is very old, like the diagonal streets in Bridgeport oriented to the river instead of true north, we can accept it as a historical legacy. When the behavior is more modern, it tends to offend fine sensibilities.

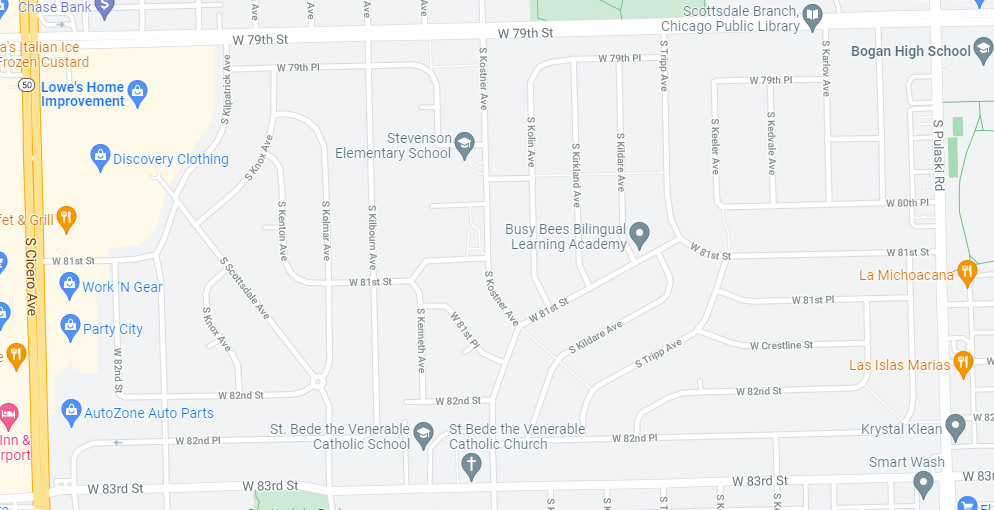

In Brennan's vision, the knowledge that State and Madison are 0EW and 0NS, coupled with the knowledge that 800 units make a mile, should allow us to navigate freely in Chicago. But when alternatives to the grid plan are employed, specific knowledge of the area is required to traverse it. That's exactly what the planners of Scottsdale (above) wanted: to be different from Chicago, though still technically part of it. Access points are severely limited, there is no street life, and everyone depends on a car. Strangers feel conspicuous, since nobody has any business in a place like this who doesn't live there or work at the mall. The decision to lay out a neighborhood like this, to opt out of the urban fabric, is a major annoyance to the idealist city planner exemplified by Brennan.

As a somewhat related issue, have you noticed that the ideal Chicago square is designed around powers of 2? Dividing the mile into eighths and sixteenths is standard: usually eighths one direction and sixteenths the other, to form long, skinny blocks bisected by alleys. It's not difficult to find areas where this template is rejected. In general, larger city blocks give a more posh feeling, and smaller blocks are scrappier, a la the urban jungle. So having streets every sixth of a mile is associated with Ravenswood and Uptown (born rich), while having streets every tenth of a mile is associated with Pilsen and Bucktown (born prole-y). You can see how this challenges Brennan's system: you may have to accept in Uptown, for instance, that 1100 West does not strictly refer to a point 1.375 miles west of State, but at least it won't be far off the mark.

A much more vexing problem relating to address numbers is found on the near south side, where reformers found it impossible to enforce the rule of "800 units per mile." I'm not entirely clear on the order of events here, but it's clear that the South Side has a long tradition of naming horizontal streets with numbers, and naturally one would like 45th Street to be equivalent to 4500S, in the same way that Addison is 3600N. When Brennan got on the job, he noticed something disturbing: too many numbered streets had been allocated to the first three miles of the south side. 12th Street (now Roosevelt) was one mile due south of Madison, 22nd Street (now Cermak) was one mile south of that, and 31st Street (still 31st) was one mile further. That means 31st should "really" be 24th (2400S), while 35th (the next half-mile street) should be 28th (2800S), and 95th (the current Red Line terminal) should be unmasked as 88th (8800S). But what could Brennan do? He'd either have to rename every last numbered street (either to proper names or the "correct" numbers), or keep the names while assigning them the wrong address numbers (i.e. a building on 32nd and Halsted would be 2501 South Halsted). Perhaps he did pursue one of these courses, but it obviously wasn't successful, because the situation hasn't changed to this day. Consequently, we can't actually trust our address math in those cases where one or both endpoints fall in the danger zone between Madison and 31st. It's not the end of the world -- the 800 rule holds true for all north, west, and east streets, and once you get past 31st, all you need to do is subtract 700 address numbers or 0.875 miles to correct for the sloppy situation. (For instance, Addison at 3600N and Pershing at 3900S are not 7500 units or 9.375 miles apart; they are 6800 units and 8.5 miles apart.) It's not too hard to remember that the major south side horizontals (47th, 63rd, 79th...) are one number less than the multiples of four (48, 64, 80). But it's a bother all the same, and another blow against idealism.

A third broad category of disappointment is the failure to achieve consistent street names for given alignments. Addison is always 3600N and 3600N is always Addison, but there are countless cases of competition, in which different names for the same alignment are used in different parts of the city, obscuring the connections between neighborhoods that are actually in horizontal or vertical alignment. Brennan and his associates worked hard to get rid of these ambiguities, but did not come close to sorting all of them out. Note how diagonal streets like Broadway and Grand move irregularly through the grid, sometimes running diagonally, sometimes "taking over" an alignment, as Broadway replaces what should be Racine at 1200W in Edgewater. Halsted, too, at 800W, is briefly taken over by Broadway; when Broadway leaves again, Halsted is renamed Clarendon down its final stretch. Kimball and Homan are both 3400W, changing names at North Avenue (a popular place to do so). Some neighborhoods, like Old Town, have a high percentage of unique street names: Larrabee is their version of Jefferson (600W), Menomonee is their Bloomingdale (1800N). The rectilinear portions of Bridgeport are generally exemplars of standard names, but the temptation to make one or two tweaks, like Lituanica over Peoria (900W), is irresistible. There is nothing wrong with local flavor, but I think it is reasonable to say that the current degree of irregularity in Chicago streets is more a result of stubbornness and inertia than of good taste and common sense.

Thinking in this spirit, I have taken the time to prepare an unofficial table of canonical street names, which assigns one proper name to every alignment in the city, as a means of establishing a baseline from which deviations and alternate names can be better remembered as such. If Brennan had taken his system to the logical extreme, a table like this one would actually be definitive. Below I excerpt a series of horizontal half-mile streets to make clear what kind of information I have collected. Remember, half-mile streets are the most important lines in the grid, and they show very little naming variation, so compiling this short list was child's play. Memorizing this sequence is a good initiation into the mysteries of Chicago geography.

| ADDRESS | NAME | COMMENT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7600N | HOWARD | ||

| 7200N | TOUHY | ||

| 6800N | PRATT | ||

| 6400N | DEVON | ||

| 6000N | PETERSON | ||

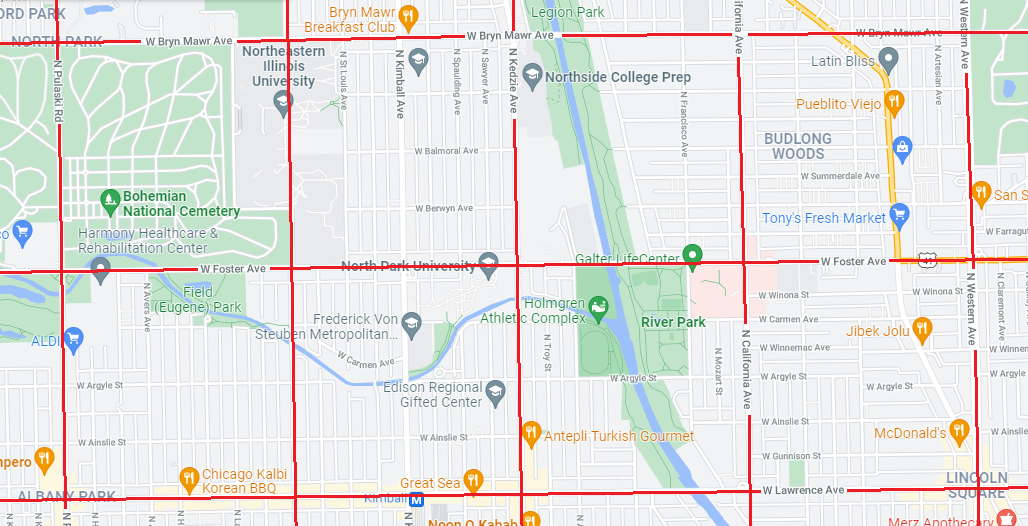

| 5600N | BRYN MAWR | ||

| 5200N | FOSTER | ||

| 4800N | LAWRENCE | ||

| 4400N | MONTROSE | ||

| 4000N | IRVING PARK | ||

| 3600N | ADDISON | ||

| 3200N | BELMONT | ||

| 2800N | DIVERSEY | ||

| 2400N | FULLERTON | ||

| 2000N | ARMITAGE | ||

| 1600N | NORTH | ||

| 1200N | DIVISION | ||

| 800N | CHICAGO | ||

| 400N | KINZIE | ||

| 0N–S | MADISON | Begin problematic zone | |

| 600S | HARRISON | ||

| 1200S | ROOSEVELT | ||

| 1600S | 16th | ||

| 2200S | CERMAK | ||

| 2600S | 26th | ||

| 3100S | 31st | End problematic zone | |

| 3500S | 35th | ||

| 3900S | PERSHING | ||

| 4300S | 43rd | ||

| 4700S | 47th | ||

| 5100S | 51st | ||

| 5500S | 55th | ||

| ... | ... | Count by fours to 135th |

One last word about the lack of coordination. I mentioned that South Side horizontals are usually numbered instead of named: 54th Street is 5400S. I was really flummoxed the first time I looked at the CTA map and found that the Pink Line ends at 54th and Cermak. Cermak is 2200S, so patently there is no corner of 54th and Cermak! I didn't realize that the Pink Line leaves Chicago to end in Cicero, which names both its vertical and horizontal streets with numbers. Thus 5400W, which Chicagoans call "Long," becomes 54th instead. I later realized that other suburbs, for instance in the Palos region, are fond of this same strategy.

No sooner had I accepted this than I noticed a third series of numbers in the near western suburbs. Brookfield Zoo is on 1st Avenue and the main drag of Maywood is 5th. Again, these streets are verticals. This system is not without its merits, as 1st can be conceived as the first street after the Des Plaines River (which, in the center of the urban region, flows basically north to south a short distance west of Harlem Avenue). But if we compare these streets to Chicago's grid system to see how they sync up, we find that 1st corresponds to 8400W -- not very memorable or significant. And these suburbs hand out one number every sixteenth of a mile; the South Side of Chicago features a new number every eighth of a mile. Obviously Brennan had no control over the west suburbs, but it's a good example of disorder and complication creeping into a logical system, just as you can find an extraordinary number of streets named "Center" and "Central" scattered throughout the city and suburbs. Entropy is the most natural thing in the world.

Here is an amusing aside that shows the dangers of too much logical order, and not enough spontaneity. Brennan had a contemporary and colleague named John Riley, a city staffer who shared a strong interest in address reform. Riley, whose job required him to pack his head with thousands of street names, with all their variants, exceptions, duplicates, and other such quirks, tried to cut his Gordian knot with an extremely logical system which, combined with Brennan's standard addresses, would surely make Chicago the most orderly city in history -- the envy of even the geomancers who laid out Genji's Kyoto. Riley knew as well as we do that mile intervals are built into Chicago's grid, and he made a simple scheme to encode geographical information in street names. He proposed that all vertical streets lying in the nth mile from the east should have a name beginning with the nth letter of the alphabet. The state line is at 4100E, an inconvenient number, so he made 3200E-4100E a slightly oversize "A" band, while 2400E-3200E was a clean mile of "B," and 1600E-2400E was "C." This was supposed to continue all the way out to 8000W-8800W, which was assigned "P." Just in time to avoid Q!

Under Riley's system, any seasoned Chicagoan who heard the address "2200 N Garibaldi" would immediately know the building was in the seventh mile: somewhere between Halsted and Ashland. Or would Halsted and Ashland have to change their names, too? Already you can see the sticking point -- it's one thing to tell a particular neighborhood that they must call their silly duplicate "Jackson" street "Dorchester" like everybody else, but telling the entire city that famous "Ashland" will henceforth be known as "Hamish," as befits the first of the H Streets, will probably suggest to voters that the current administration has too much time on its hands.

Riley's proposal was not totally dismissed, however. It was too late to talk about bulk renaming in the city center (where, as we know, many local variant names were allowed to survive), but Riley was just in time to influence the development of the relatively low-density western neighborhoods, which were still fairly malleable, and a good place to try the experiment. There is no band of A streets, or B, C, D, or even H, I, J, but suddenly, crossing Pulaski (4000W), the traveler enters "K Town." Most, but not all, of the vertical streets in this mile band are indeed tributes to the 11th letter. Kildare and Kilbourn are nice (though, come to think of it, the mile between Pulaski and Cicero has nearly zero Irish heritage), but it's not likely that Kedvale and Kolmar would have graced Chicago street signs if not for necessity. West of Cicero, K gives way to L, M, N, O, and P, with varying degrees of success. The system is hamstrung by the fact that neither do all streets in a given band conform to the rule, nor are all streets conforming to the rule found in the proper band. Lowell, Oak Park, and Parkside, for instance, are false friends which are not found where they ought to be.

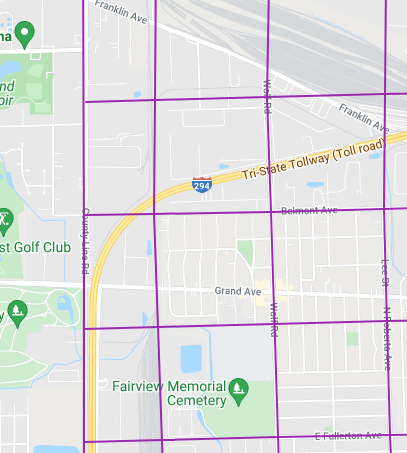

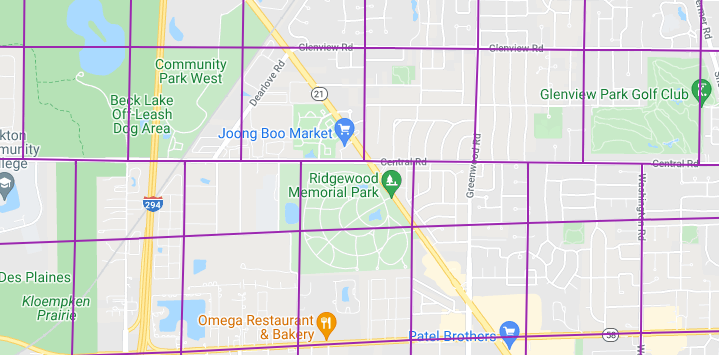

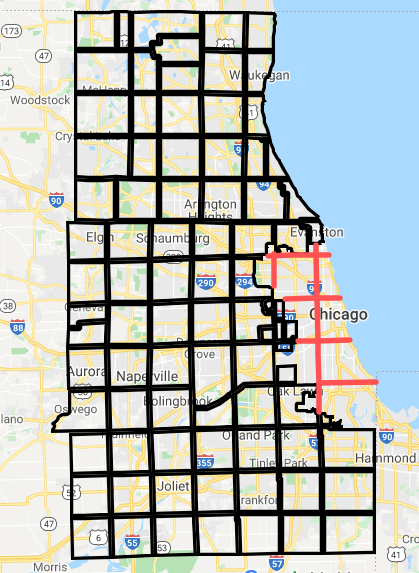

Let me circle back to the concept of a township, which I defined as a constituent unit of a county. A typical township is a square six miles on each side, containing thirty-six sections of 640 acres each. The Chicago metropolitan area is split across several counties, but a fairly neat grid is observable, with allowances for strange behavior near the lakeshore and other places. Most of these townships are standard, and most of the rest are standard townships widened or shortened by a couple of miles. Note the prominent dogleg in the north which resets the grid. To examine this map in more detail, visit my interactive Google map (not official, but reasonably accurate).

The pink lines crossing the city proper indicate that formerly existing townships, or townships that would logically exist based on the orientation of nearby townships, are no longer extant. This is what I wanted to mention -- when a township has served its purpose of facilitating the orderly sale of land parcels, it becomes something of a fossil artifact. A Chicago resident already votes for an alderman, a mayor, a congressman, a senator, a state senator and representative, a governor, a county board president, a state's attorney, water reclamation commissioners, judges, and so on and so forth. Why does she need to worry about a township administrator? The townships that formerly composed Chicago have been collapsed into purely symbolic territories that are only referenced in real estate matters. The property tax assessor, for instance, may find it convenient to audit data at the township level, since that is how his predecessors gathered it.

Suburban townships, on the other hand, are still alive and kicking, and they do have administrative functions, though these are constantly under attack in a cash-strapped state like Illinois. As you travel around the region you may encounter a Township high school or a Township public health center. You may elect a Township supervisor and be entitled to receive modest cash assistance through Township-operated relief programs funded by the tiny but non-zero percentage of your tax bill that goes to fund the Township's operations.

I have a strange affection for townships. They are the missing link between Chicago's grid and America's grid. Before you know what they are, you wonder why the heck there are so many references to "Maine" around Des Plaines. Green Garden, Leyden, Proviso, New Trier, Ela, and Cuba are places you can pass through without knowing it. Finding a map of townships is therefore a bit like finding a secret blueprint.

There are several subjects in Chicago geography upon which I have not even touched, especially the business of rivers and their changing directions, the Indian Boundary lines, the old roads and trails, and a sense of the order in which development proceeded. For now just let me mention a fact about the maps in my journal which it has not been convenient to place elsewhere.

My division of the territory into LAND and CITY for the purpose of sorting my pictures is original, and it is not very meaningful in any context outside of my site. Every border is a river, except Dempster across the top; I preferred using these natural borders over municipal ones, and some awkward results were unavoidable. For instance, the entirety of North Palos Forest is part of CITY, but the neighborhoods of East Side, Hegewisch and Riverdale are not. O'Hare Airport is technically Chicago but not CITY; the O'Hare neighborhood further east, though, is included. I hope these quirks are not taken as carelessness or a value judgment. Ultimately the difference between CITY and LAND is in the attitude required for a successful walk. Late nights at Wolf Lake, waiting all alone for an elusive #30 bus, with coyotes howling from the direction of the old missile silo, were a key factor in the decision to cut that southeast side loose.

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |